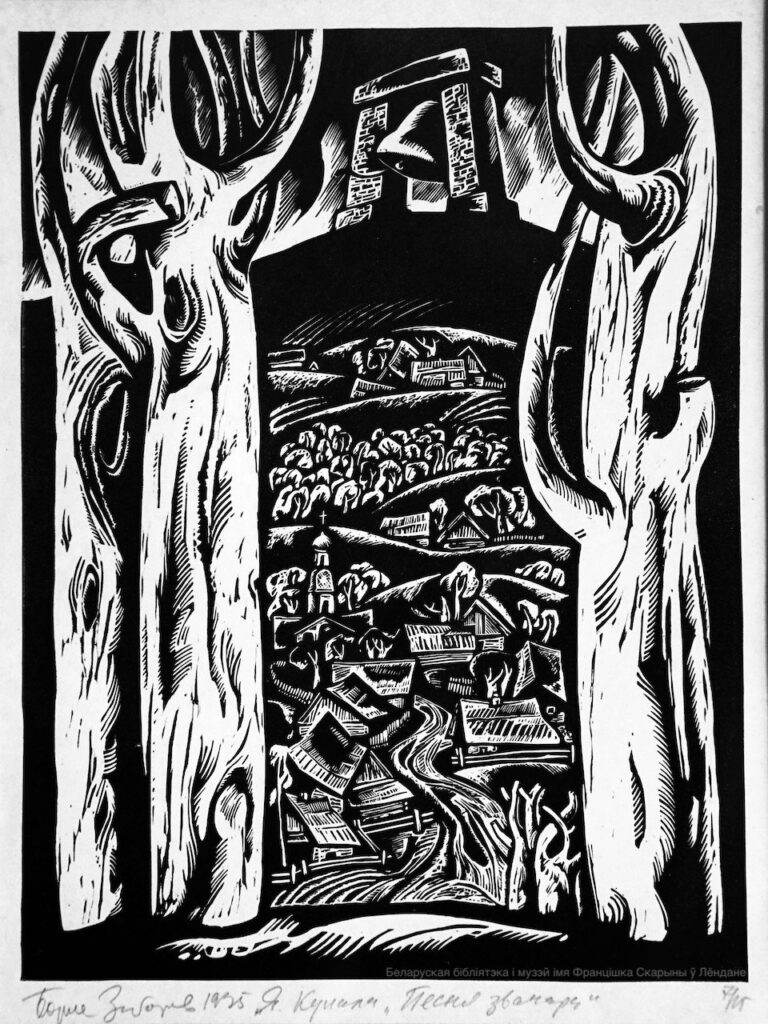

Лінагравюра Барыса Заборава “Янка Купала”, ілюстрацыя да зборніку “Выбраная лірыка” (Менск, 1967), падараваная Скарынаўскай бібліятэцы аўтарам.

●

Янка Купала нарадзіўся 140 гадоў таму – 7 ліпеня (па новым стылі) 1882 г. Нарадзіўся на Купалу – ці Купальле, – таму і псэўданім узяў сабе такі. Сям’я ягоная ня была заможная, але й не жабравалі: бацькі часта перабіраліся ад фальварка да фальварка, ад пана да пана, дзе арандавалі зямлю. Янку яны далі добрую, хоць і простую, адукацыю – ад вандроўных настаўнікаў і ў народных вучэльнях. І доступ да кніжак у яго быў – навакольныя людзі мелі бібліятэкі.

Янка пачынаў пісаць паэзію па-польску, першыя вершы свае надрукаваў па-польску таксама. А трапілі яму ў рукі кніжкі Багушэвіча і Дуніна-Марцінкевіча, то ўразіўся ён моцна, што па-беларуску ствараць можна прыгожую літаратуру. І ўжо назад не азіраўся пясьняр.

Слава Купалу заслужана прыйшла амаль вокамгненна. На яго раўняліся і ім натхняліся. Але ягонае жыцьцё не было бестурботным. У Савецкай Беларусі яго то насілі на рукох, то вінавацілі ў контррэвалюцыйнай “нацдэмаўшчыне”. На ягоных вачох закатавалі тысячы таленавітых і самых простых людзей. З-за невыноснага ціску ў 1930-м годзе ён спрабаваў забіць сябе. Але збольшага трымаўся, ствараў цудоўную паэзію, разьвіваў новыя тэмы і жанры, падтрымліваў іншых творцаў.

Каб сёньня Купала быў з намі, вядома, як ён адказаў бы на пытаньне –

Чаму ў сэрцы беларускім

Песьня Тарасова

Адгукнулася, запела

Зразумелым словам?

Бадай, як сотні тысячаў суайчыньнікаў, яго б таксама выціснулі зь Беларусі:

Бо йшла доля беларуса

З доляй украінца

Адналькова — ў поце, ў сьлёзах,

Церневым гасьцінцам.

(“Тарасова доля”)

У жыцьці Купалы мы лёгка бачым і свае жыцьці, і цэлы народ. Як і ягоная сям’я, мы працуем цяжка і без асаблівых гарантыяў, самааддана гадуем дзяцей, зрываемся ў пошуках лепшае долі да суседніх народаў і ў далёкія землі. Раз-пораз адкрываем для сябе каштоўнасьці, пра якія раней не задумваліся, якія раптам зьмяняюць усё. Як Купала, мы прыстасоўваемся да таго, што зьмяніць ня можам, і пакутуем ад гэтага. Зрэшты, сярод поту і сьлёзаў знаходзім прычыны для радасьці.

Купала паказаў нам, што беларушчына не пачынаецца і не заканчваецца ідэалёгіяй. Яна – як паветра, ёй можна дыхаць лёгка, амаль незаўважна для сябе. А тая – напаўняе лёгкія жыцьцядайнай сілай.

A linocut Janka Kupała by Barys Zaboraŭ, included in the compilation Selected Lyrics (Minsk, 1967), which the artist donated to the Skaryna Library.

●

Janka Kupała was born 140 years ago – on 7 July 1882 – on the Kupała (or Kupalle) day; this led him to his pen name. His family was not wealthy, but they did not beg either: parents often moved from farm to farm, from lord to lord, where they rented land. They gave Janka a good, albeit simple, education – from travelling teachers and in primary schools. He had access to books – wealthier neighbours often had libraries.

Kupała began to write poetry in Polish, his first published poems were in Polish as well. Once he came across the books of Bahuševič and Dunin-Marcinkevič, he was deeply impressed that fine literature could be created in Belarusian too. He never looked back.

Fame came to Kupała almost instantly. Many looked up to him and were inspired by him. But his life was not carefree. In the BSSR, he was either praised or accused of counter-revolutionary nationalism. Thousands of people perished in Stalin’s purges before his eyes. Due to unbearable accusations, he tried to kill himself in 1930. Despite all the pressure, he held on, created wonderful poetry, developed new themes and genres, and supported other creators.

If Kupała were with us today, we know how he would answer the question which refers to the most prominent Ukrainian poet, Taras Shevchenko:

Why did Taras’s song / echo, sang / in the hearts of Belarusians / with understandable words?

Perhaps, like hundreds of thousands of our compatriots, he would also be forced out of Belarus:

Because the fate of the Belarusian / together with the fate of the Ukrainian / – in sweat, in tears walked / along the thorny road.

(Poem Tarasova dola, 1939)

In the life of Kupała, we recognise our own lives and the whole nation. Like his family, we often work hard, selflessly raise children, and leave for neighbouring countries and distant lands for a better life. Occasionally, we discover unexpected values that we hadn’t thought about before, which suddenly change everything for us. Like Kupała, we adapt to what we cannot change and suffer from it. Amid sweat and tears, we also find the reasons for joy.

Kupala showed that Belarusian identity does not equal ideology. It is like air: we can breathe it easily, almost imperceptibly for ourselves. It empowers us.

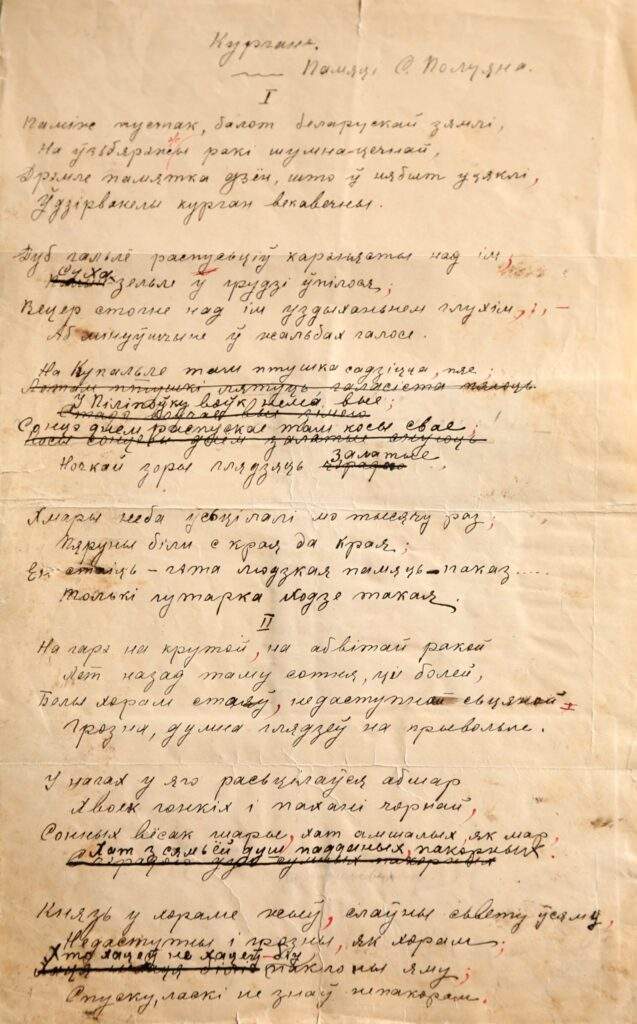

Паэма “Курган” / Poem Kurhan (The Mound)

21 чэрвеня 1912 у газэце “Наша Ніва” была ўпершыню надрукаваная паэма Янкі Купалы “Курган”.

Поўны рукапіс гэтага твору захоўваецца ў Скарынаўскай бібліятэцы. Ён быў перададзены сюды беларускім грамадзкім дзеячом у ЗША Леанідам Галяком.

●

110 years ago, on 21 June 1911, the newspaper Naša Niva published Janka Kupała’s poem Kurhan (The Mound).

Our Library preserves its complete manuscript. It was donated to the Library by Leanid Halak, a Belarusian public figure in the USA.

“Жалейка” – першы зборнік песьняра / Žalejka (The Hornpipe) – The First Book

Першы зборнік паэзіі Янкі Купалы “Жалейка” быў апублікаваны ў Санкт-Пецярбургу ў 1908 годзе. На здымку – вокладка першага выданьня зборніка, асобнік якога захоўваецца ў нашай калекцыі.

●

The first book of poems Žalejka (The Hornpipe) by Janka Kupała was published in Saint-Petersburg in 1908. The first edition of this book is preserved in our collection.

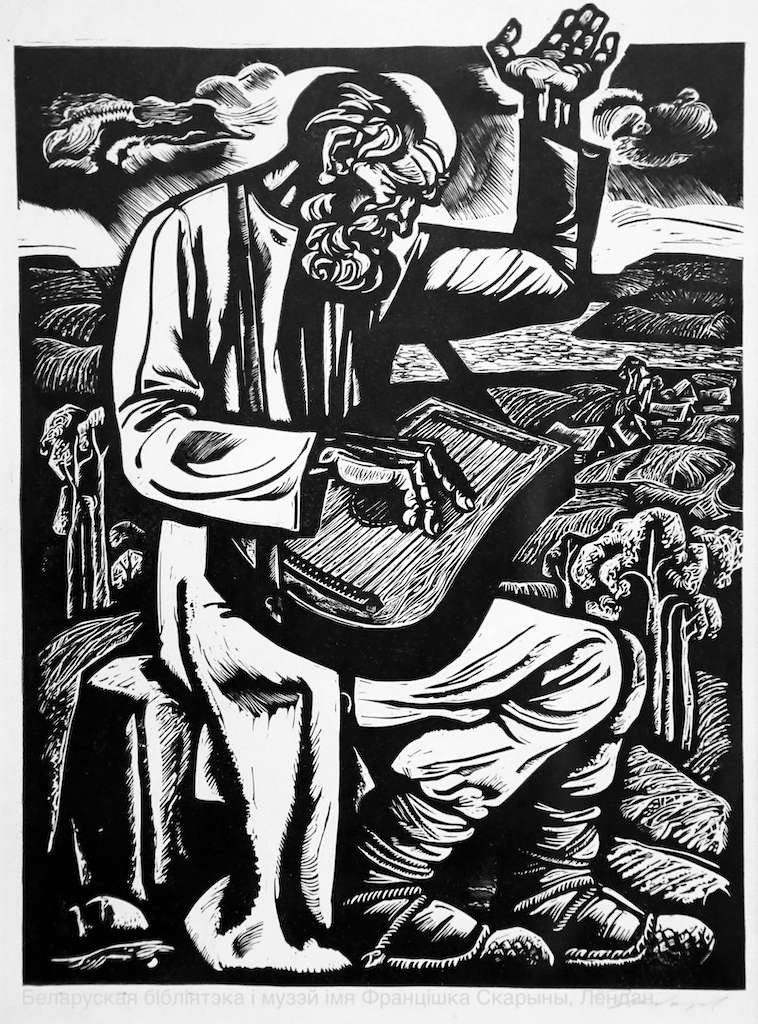

Паэма “Гусьляр” / Poem Huśliar (The Gusli Musician)

Лінагравюра Барыса Заборава, якую мастак перадаў бібліятэцы, – ілюстрацыя да верша Янкі Купалы «Гусьляр» у томіку «Выбраная лірыка» (Менск, 1967).

●

A linocut by Barys Zaboraŭ, which the artist donated to the Skaryna Library – an illustration to Janka Kupała’s poem Huśliar (The Gusli Musician), included in the compilation Selected Lyrics (Minsk, 1967).

Упершыню верш «Гусьляр» зьявіўся ў аднайменным зборніку (Пецярбург, 1910), а быў напісаны некалькімі гадамі раней, калі ўжо было зразумела, што рэвалюцыя 1905 году заканчваецца паразай. У гэтым кантэксьце Купалавыя словы перагукаюцца і з нашым часам: ён заклікае гусьляра будзіць сьвет да новага паходу, да новага жыцьця.

Ты ад гумн да гумн

Запануй, гусляр!

Дай паходням жар,

Лінь жыццё ў бор-яр,

Не мінай акон;

Строй ваякаў шар,

Кроў сагрэй, як вар,

Сказам новых дзён…

Грай, будзі, гусляр!

●

The poem Huśliar was first published in the compilation of the same name (St. Petersburg, 1910). It was written a few years earlier when it became clear that the 1905 revolution in the Russian Empire ended in defeat. In this context, Huśliar words resonate with our time: he calls on the gusli musician to awaken the world to a new campaign, to a new life.

From barn to barn

You reign, Huśliar!

Give the torches heat,

And life to woods-ravines,

Don’t omit any windows;

A formation of warriors align,

Warm the blood like brew,

With the words of new days …

Play, awake them, Huśliar!

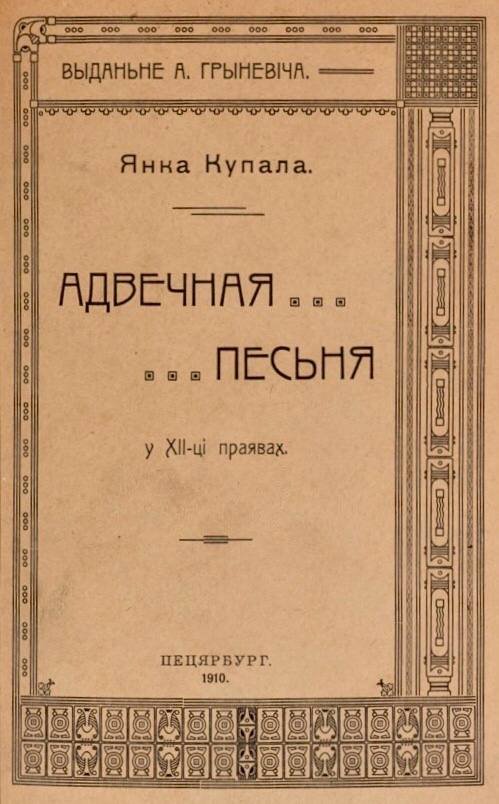

Паэма “Адвечная песьня” / Poem Adviečnaja Pieśnia (The Eternal Song)

Асобнік першага выданьня (Санкт-Пецярбург, 1910) “Адвечнай песьні” з калекцыі Скарынаўскай бібліятэкі.

●

Янка Купала працаваў у бібліятэцы – гэта праўда! У 1908 г. браты Луцкевічы выцягнулі яго ў Вільню, дзе ён уладкаваўся ў прыватную бібліятэку “Знание”. І адначасова супрацоўнічаў зь першым беларускім штотыднёвікам “Наша ніва”. У Вільню ён прыехаў з тэкстам створанай незадоўга перад тым паэмы “Адвечная песьня” – сваім першым драматычным творам, напісаным вершам. У ёй жыцьцё чалавека, мужыка-селяніна паўстае даволі змрочным і пэсымэстычным:

Раскрыйся нанова, магіла:

Страшней цябе людзі і свет.

Год, праведзены ў Вільні, быў вельмі станоўчым для Купалы: ягоная паэзія тут пачала набываць асаблівую красу і сілу. “Наша Ніва” з захапленьнем піша, што «перад Купалам вялікая будучыня».

A copy of the first edition (St Petersburg, 1910) of Adviečnaja Pieśnia (The Eternal Song) from the Skaryna Library collection.

●

Janka Kupała worked in the library – it’s true! In 1908, the Luckievič brothers invited him to move to Vilna where he worked at the private library Znaniye. At the same time, he collaborated with the first Belarusian weekly, Naša Niva. He arrived in Vilna with the recently written dramatic poem Adviečnaja Pieśnia (The Eternal Song) – his first dramatic work in verse. In this poem, the life of a man, a peasant, portraited gloomy and pessimistic:

Reopen again, grave:

People and the world are scarier than you.

The year spent in Vilna was very happy for Kupała: his poetry here began to acquire a remarkable beauty and breadth. Naša Niva enthusiastically wrote that “Kupała is facing a great future.”

Верш “Песьня званара” / Poem Pieśnia Zvanara (The Song of the Bell Ringer)

Лінагравюра Барыса Заборава “Песьня званара” – ілюстрацыя да аднайменнага верша Янкі Купалы, які ўвайшоў у зборнік “Выбраная лірыка” (Менск, 1967), – была падараваная Скарынаўскай бібліятэцы аўтарам.

●

Bаrys Zaboraŭ’s linocut Pieśnia Zvanara (The Song of the Bell Ringer), an illustration to the homonymous poem by Janka Kupała (part of the compilation Selected Lyrics, Minsk, 1967), was donated to the Skaryna Library by its author.

У “Песьні”, якая была напісаная ў 1909 годзе, Купала ізноў вяртаецца да вобразу песьняра, прарока, які будзіць народ:

І завешу я звон, з усіх чутны старон —

Раўня голас і віхру, і грому.

Як пушчу яго ў ход, склічу ўміг карагод,

Ні адзін не заседзіцца дома!

Разгудзіцца мой звон ад акон да акон,

Душы збудзіць, па сэрцах удара,

Дрогнуць сковы цямніц, бліснуць іскры зарніц,

Заварушацца яры, папары.

Пад “Песьню” была напісаная музыка, і яна сьпявалася некалі папулярным гуртом “Песьняры”. https://youtu.be/CbmuRx-HBLw

●

In the “Song” written in 1909, Kupała returns to the image of the singer (“pieśniar”), the prophet who awakens the people:

And I’ll put up a bell, to be heard from all sides –

An equal voice both to whirlwind and thunder.

When in motion it’s set, it will summon a dance,

Round dance, no one will sit at home!

And from window to window my bell will be heard,

Awakening souls and striking hearts,

Shaking shackles of dungeons, setting sparks of lightning flash,

Stirring ravines and ferns-covered forests.

The poem has been set to music and цфы performed by the once-popular Belarusian band Pieśniary.

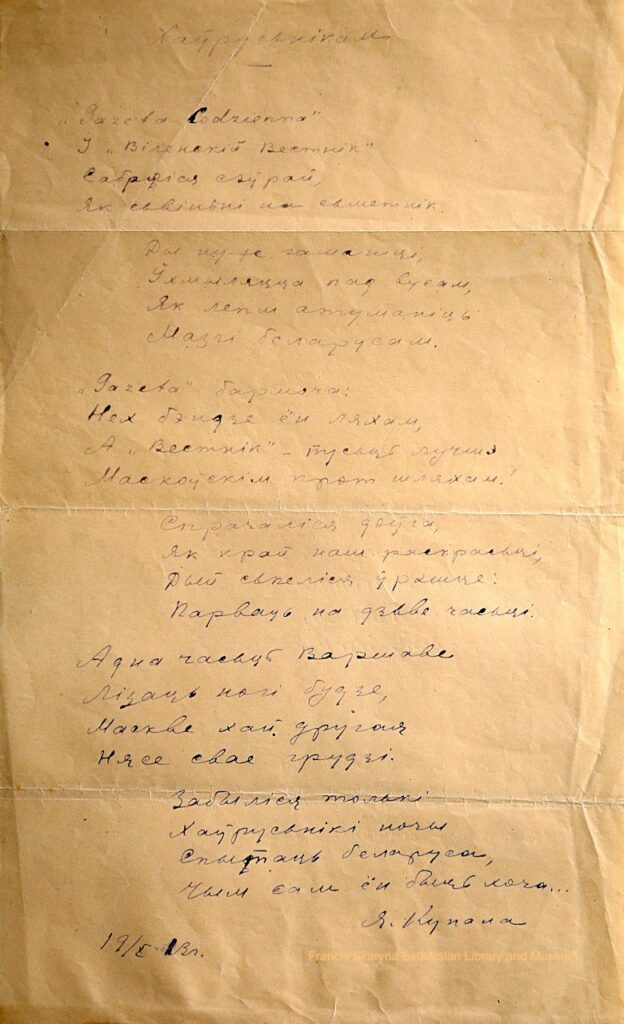

Верш “Хаўрусьнікам” / Poem Chaŭruśnikam (To the Allies)

Рукапіс верша, падпісаны “Янка Купала”, быў перададзены ў Скарынаўскую бібліятэку беларускім грамадзкім дзеячом у ЗША Леанідам Галяком. Цікава, што пры публікацыі верша ў часопісе “Полымя” у 1929 годзе верш падпісаны псэўданімам “Цімох Каруз”.

●

The poem’s manuscript signed ‘Janka Kupała’ was donated to the Skaryna Library by Leanid Halak, a Belarusian public figure in the US. An interesting fact is that when this poem was published in the literary journal Polymia (The Flame) in 1929, it was signed under the pen name ‘Cimoch Karuz’.

У 1913 годзе Янка Купала напісаў верш “Хаўрусьнікам”, у якім асудзіў усходніх і заходніх суседзяў, што мелі пляны на беларускія землі. Паэт надзвычай дакладна прадказаў расейска-польскі падзел Беларусі, які адбудзецца па Рыскай Дамове праз восем год:

Адна часьць Варшаве

Лізаць ногі будзе,

Маскве хай другая

Нясе свае грудзі.

Забыліся толькі,

Хаўрусьнікі ночы,

Спытаць беларуса,

Чым сам ён быць хоча.

●

In 1913 Janka Kupała wrote his poem Chaŭruśnikam (To the Allies) in which he condemned the eastern and western neighbours coveting Belarusian lands. The poet remarkably accurately predicted the Russian-Polish partition of Belarus, which would take place following the Peace of Riga eight years later:

One part is given to Warsaw

To lick their boots,

The other is going

To suckle Moscow.

But what they forgot,

The allies of the night,

Is to ask the Belarusian

What he wants to be.

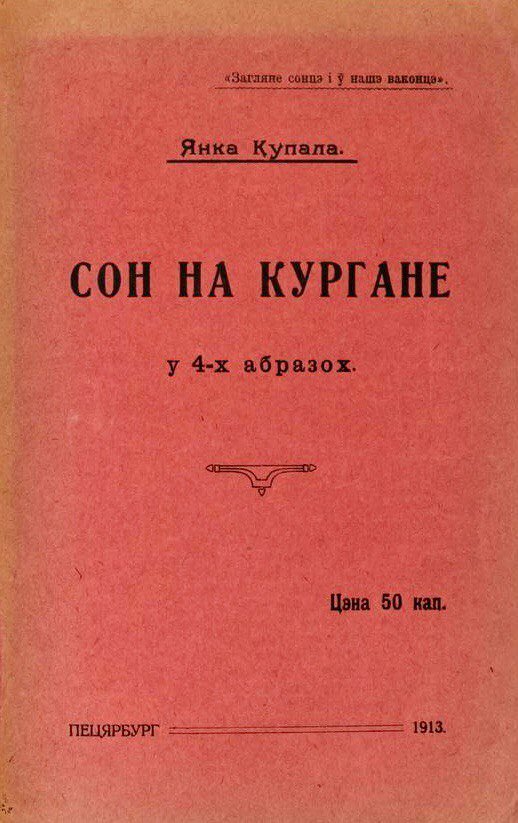

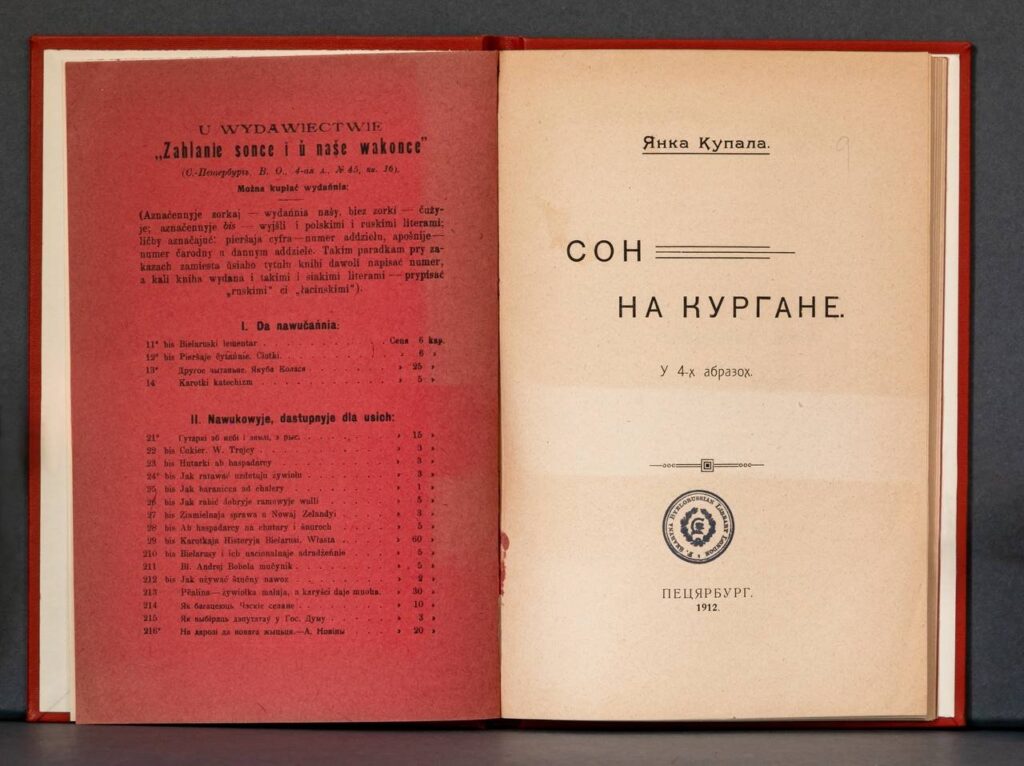

Паэма “Сон на кургане” / Poem Son na kurhanie (A Dream on a Mound)

Асобнік першага выданьня паэмы «Сон на кургане» (Санкт-Пецярбург, 1913), домам якога зьяўляецца бібліятэка імя Францішка Скарыны.

●

Як многія творы Купалы, драматычная паэма “Сон на кургане” моцна перагукаецца з нашым часам. Яна была напісаная ў гады рэваншу расейскіх уладаў пасьля паразы рэвалюцыі 1905 г. – у часы масавых арыштаў і ваенна-палявых судоў. Тыя парадкі Купала пазьней назваў «царствам ночы і цемры». Многія дзеячы беларускага руху сядзелі па турмах ці былі высланыя ў Сыбір, якіх-колеч выразных пэрспэктыў на паляпшэнне жыцьця і спыненьня рэпрэсіўнай машыны не праглядалася.

…Вырвалі шчасце, вырвалі вочы,

Думы паганяць няславай;

Сцежкі заслалі цемраю ночы,

Рыюць у процьму канавы.

Тутка мы п’яны, ах, п’яны

Вечным пракляццем сваім:

Гоячы вечныя раны,

Новыя раны тварым.

Твор не абмяжоўваецца водгукам на пасьлярэвалюцыйныя падзеі. Паэма – цудоўны прыклад рамантызму ў Купалавым выкананьні. Яна кліча людзей і ўвесь народ на самапазнаньня, вяртаньня ў памяць роду і абуджэньня духоўных сілаў. Ейная мова – поўная сымбалізму і алегорыяў, так уласьцівых гэтаму жанру.

A copy of the first edition of the poem Son na kurhanie (A Dream on a Mound; St Petersburg, 1913) is preserved in the Skaryna Library in London.

●

Like many of Kupała’s works, the dramatic poem Son na kurhanie (A Dream on a Mound) strongly resonates with our time. It was written during the years of the revenge of the Russian authorities following the defeat of the 1905 revolution – during the time of mass persecution and military courts. Kupała later called that regime “the kingdom of night and darkness.” Many members of the Belarusian movement were imprisoned or exiled to Siberia, there were no clear prospects for a better life and ending the repressive machine.

…They tore out happiness, they tore out their eyes, / Thoughts are soiled by the failure; / The paths got obscured by the night darkness, / They dig ditches with no end to be seen.

Here we are drunk, ah, drunk / By our eternal damnation: / While healing eternal wounds, / The new ones we cause.

The content of the poem is not limited to a response to post-revolutionary events. It is a wonderful example of Kupała’s romanticism. He calls people and the whole nation to self-discovery, to recover the people’s memory and to awaken its spiritual forces. His language is full of symbolism and allegories so characteristic of this genre.

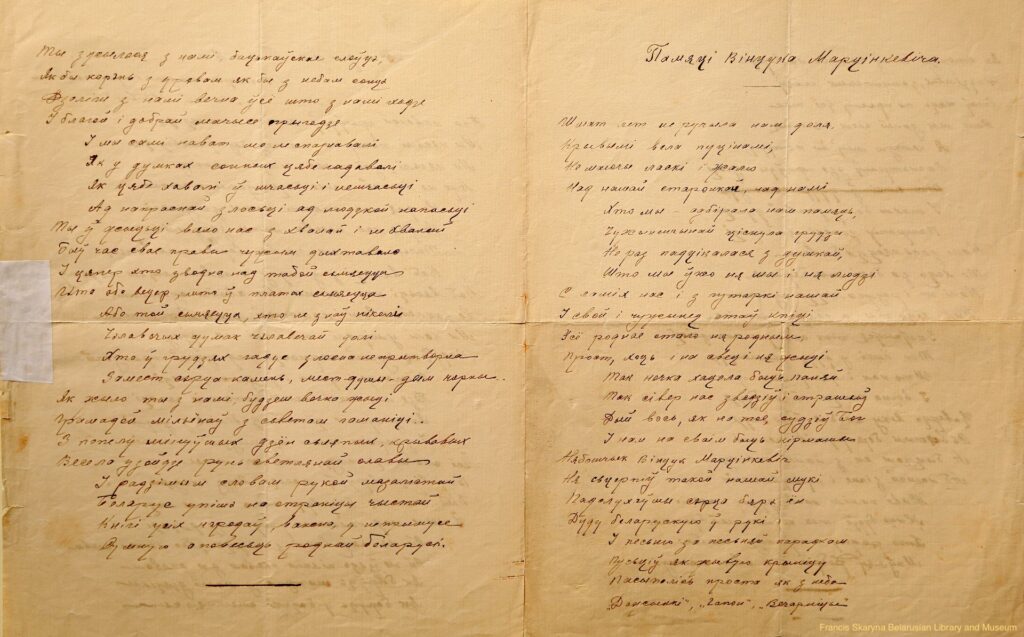

Верш “Памяці Вінцука Марцінкевіча” / Poem Pamiaci Vincuka Marcinkieviča (In Memory of Vincuk Marcinkievič)

Сярод аўтографаў Купалы, якія перадаў Скарынаўскай бібліятэцы Леанід Галяк, ёсьць рукапіс верша «Памяці Вінцука Марцінкевіча». Напісаны на 25-годзьдзе з дня сьмерці Вінцэнта Дуніна-Марцінкевіча, аднаго з пачынальнікаў новае беларускае літаратуры, верш быў упершыню надрукаваны ў “Нашай ніве” ў 1910 г. разам зь іншымі матэрыяламі, прысьвечанымі пісьменьніку. У вершы выразна гучыць тэма пераемнасьці: Дунін-Марцінкевіч для Купалы – беларускі дудар, які першы “стаў сеяць па-свойску ўсё тое, што мы далей сеем сягоння”.

Пазьней, у 20-я гады, Купала перакладзе на беларускую польскамоўныя вершаваныя ўрыўкі з камэдыі Дуніна-Марцінкевіча “Ідылія”.

Among the autographs of Janka Kupała, which were donated to the Skaryna Library by Leanid Halak, is a manuscript of the poem Pamiaci Vincuka Marcinkieviča (In Memory of Vincuk Marcinkievič). Written on the 25th anniversary of the death of Vincent Dunin-Marcinkievič, one of the founders of the new Belarusian literature, the poem was first published in the Naša Niva newspaper in 1910 along with other materials dedicated to the writer. The theme of continuity is clearly noticeable in the poem: Dunin-Marcinkievič for Kupała is a Belarusian dudar (bag-piper), who first “began to sow in his own way all that we continue to sow today.”

Later, in the 1920s, Kupała translated into Belarusian the Polish-language verse excerpts from Dunin-Marcinkievič’s comedy Idylija (Idyll).

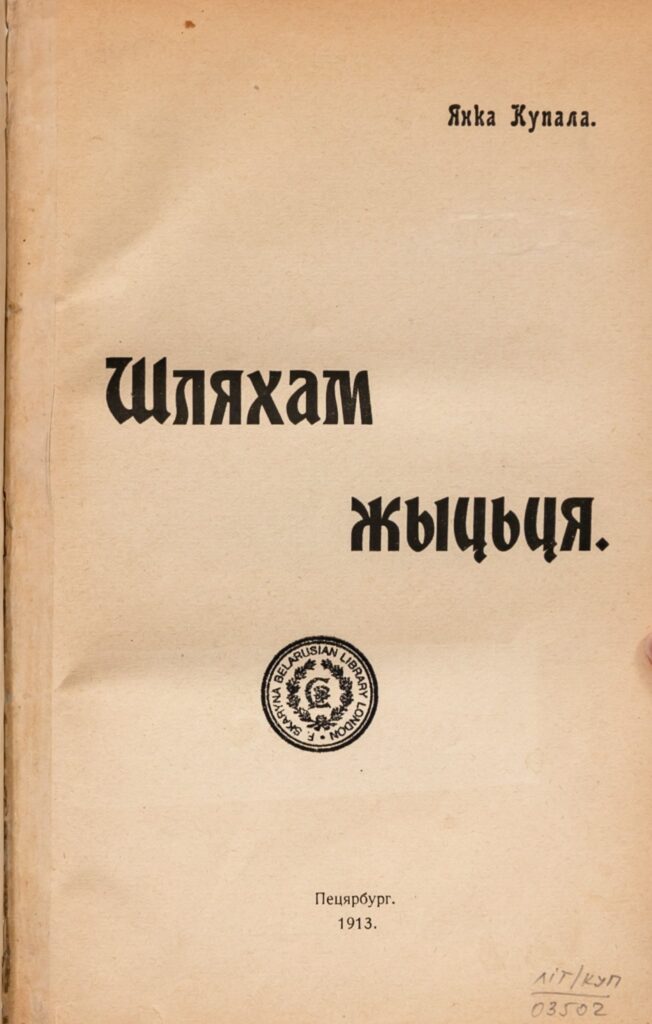

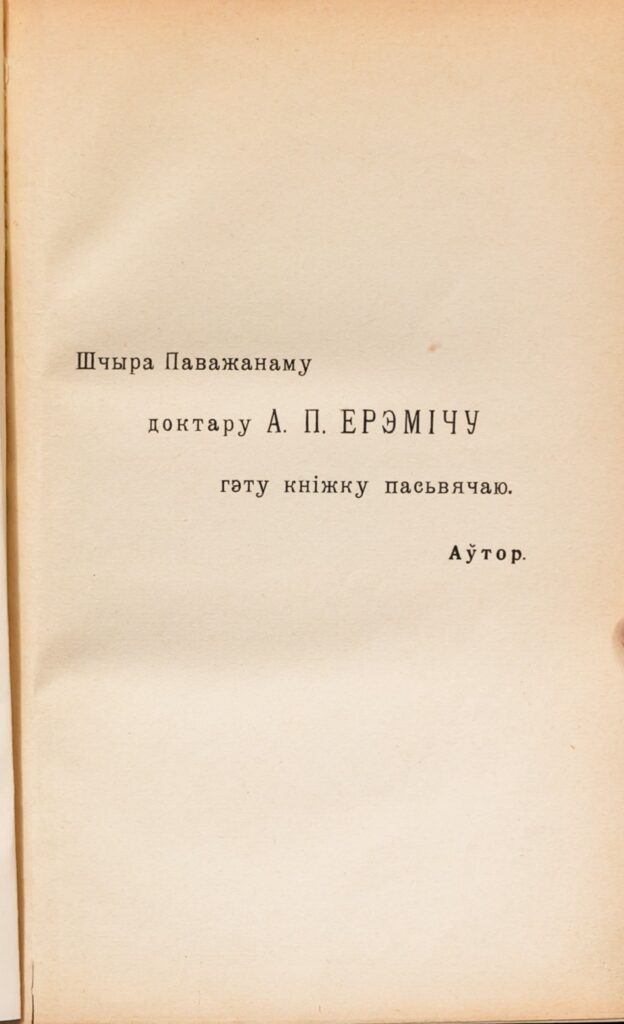

Зборнік “Шляхам жыцьця” / Book Šliacham žyccia (On Life’s Journey)

Зборнік вершаў “Шляхам жыцьця” быў апублікаваны ў Санкт-Пецярбургу ў 1913 годзе і прысьвечаны хірургу і мецэнату Аляксандру Ярэмічу, які за ўласныя грошы выдаў зборнік. Адзін з асобнікаў гэтага выданьня таксама мае сваё пачэснае месца на паліцах нашае бібліятэкі.

Сёньня, калі мы ізноў шукаем шляхі да беларускага нацыянальнага адраджэньня, заклік купалаўскага прарока “уставаць, ісьці, ноч расьсьвятляць” ня менш актуальны, як у часы Купалы.

Пара у рукі браць паходні,

Ўставаць, ісьці, ноч расьсьвятляць!

Бо што не возьмеце сягоньня,

Таго і заўтра вам не ўзяць.

Назло крывавым перашкодам

Скідайце ёрмы, клічце сход

І дайце знаць другім народам,

Які вы сільны йшчэ народ!

(верш «Прарок»)

Janka Kupała’s compilation of poems Šliacham žyccia (On Life’s Journey), published in St. Petersburg in 1913, was dedicated to the surgeon and philanthropist Aliaksandr Jaremič, who funded the publication. A copy of this publication has its place of honour on the shelves of our library.

Today, when we are once again looking for ways for Belarusian national revival, the call of Kupała’s prophet to “rise up, go, light up the night” is no less relevant than in the days of Kupała:

It’s time to take up torches, / Rise up, go, light up the night! / If you don’t take them all today, / You won’t get them tomorrow.

In spite of bloody obstacles / Drop the yokes, congregate / And let all other nations see / What a strong people you are!

Poem Prarok (The Prophet)

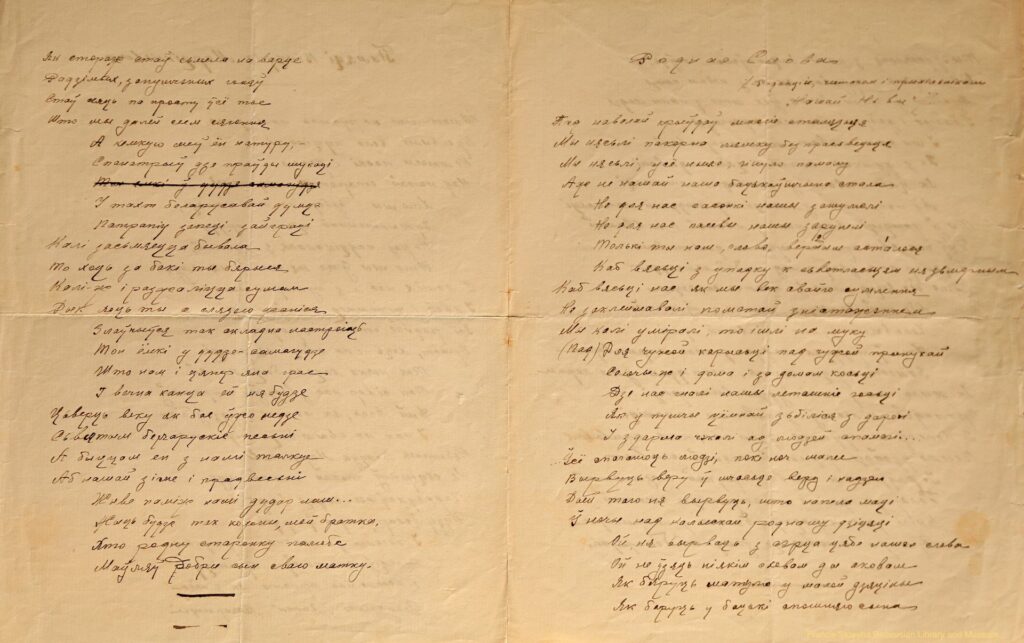

Верш “Роднае слова” / Poem Rodnaje słova (Native Word)

Сярод пэрлінаў калекцыі Янкі Купалы ў Скарынаўскай бібліятэцы захоўваецца аўтограф верша “Роднае слова”. Верш зьявіўся ў “Нашай ніве” (1910, №51) пасьля таго, як ІІІ Дзяржаўная дума Расейскай імпэрыі забараніла навучаць украінскіх і беларускіх дзяцей на роднай мове. Як і ўся творчасьць Купалы, верш напоўнены любоўю да роднае мовы і сьцьвярджае ейную вырашальную ролю ў захаваньні беларускай ідэнтычнасьці ў часы, калі “не нашай наша бацькаўшчына стала”.

Пад навалай крыўдаў многія сталецьця

Мы нясьлі пакорна лямку безпрасьвецьця.

Мы нясьлі, усё ныла, гінула памалу

Аж не нашай наша бацькаўшчына стала.

Не для нас сасонкі нашы зашумелі

Не для нас пасевы нашы зарунелі

Адно ты нам, слова, верным асталося,

Каб вясьці з упадку к сьветласьцям нязьмерным.

Цікава, што гэтыя радкі, пададзеныя паводле рукапісу, напісаныя клясычным правапісам і адрозьніваюцца ад пазьнейшых публікацыяў. Рукапіс верша перададзены Скарынаўскай бібліятэцы Леанідам Галяком, беларускім грамадзкім дзеячом у ЗША.

Among other pearls of Janka Kupała’s heritage, the Skaryna Library preserves an autograph of the poem Rodnaje Słova (Native Word). The poem was published in the Belarusian newspaper Naša Niva (1910, No. 51) after the Third State Duma of the Russian Empire forbade teaching Ukrainian and Belarusian children in their native language. Like all of Kupała’s work, the poem is filled with love to the mother tongue and affirms its unique importance for the preservation of Belarusian identity in times when “our homeland has become not ours.”

Under a blizzard of grievances for so many centuries

We obediently carried a yoke of hopelessness.

While we carried it, all ached and decayed slowly

Our fatherland is no longer ours.

No longer for us our pine trees rustle

No longer for us our harvests yield

But our word has remained faithful

To lead us from decline to great brightness.

It is interesting that these lines in the manuscript were written in classical Belarusian spelling and differ from later publications. A manuscript of the poem was handed over for preservation to the Skaryna Library by Leanid Halak, a Belarusian public figure in the US.

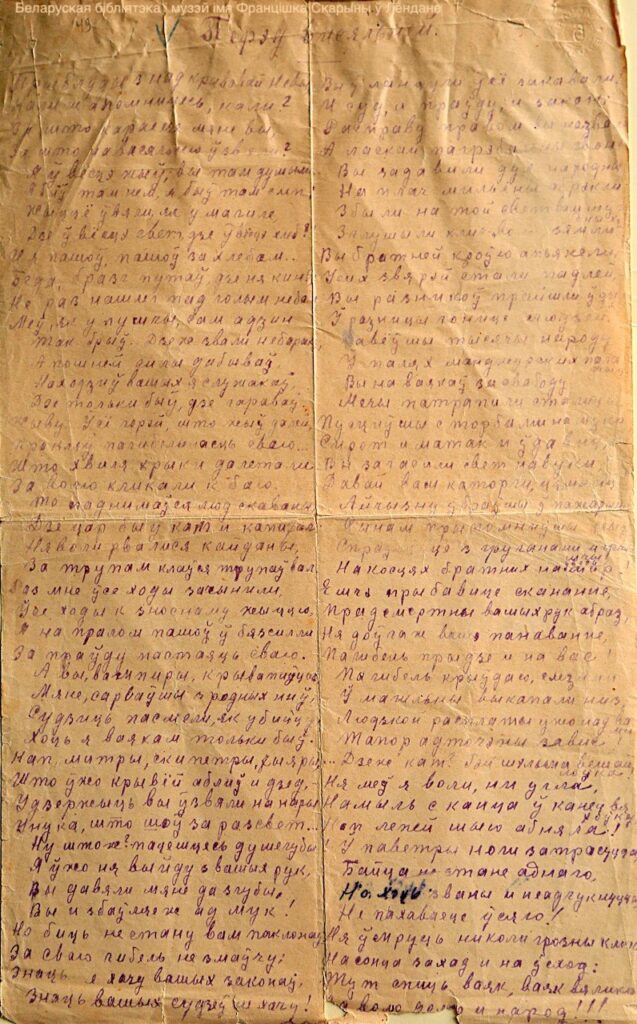

Верш “Перад вісельняй” / Poem Pierad Visielniaj (In Front of the Gallows)

Рукапіс верша быў перададзены ў Скарынаўскую бібліятэку беларускім грамадзкім дзеячом у ЗША Леанідам Галяком.

●

The manuscript of the poem was donated to the Skaryna Library by Leanid Halak, a Belarusian public figure in the United States.

28 чэрвеня 1942 году Янкі Купалы ня стала. Таямніца ягонай сьмерці дагэтуль не раскрытая. Радкі з купалавага верша “Перад вісельняй” гучаць з асабліваю сілай сёньня, у 80-ю гадавіну ягонае сьмерці.

Ну, што ж,— пацешцесь, душагубы.

Я ўжо ня выйду з вашых рук,—

Вы давялі мяне да згубы,

Вы і збаўляеце ад мук.

Але ня стану біць паклонаў,

За сваю гібель не змаўчу;

Знаць не хачу вашых законаў,

Знаць вашых судзьдзяў не хачу!

●

On 28 June 1942, Janka Kupała died in Moscow in suspicious circumstances. The lines from Janka Kupała’s poem Pierad Visielniaj (In Front of the Gallows) resonate with us particularly poignantly today, on the 80th anniversary of his death.

Well, rejoice you, murderers.

Will not escape your hands –

As you brought me to destruction,

You should save me from torment.

But I will not bow down to you,

Nor will I stay silent in my death;

I don’t want to learn your laws,

I have no wish to know your judges!

Электронную выставу да 140-годзьдзя Янкі Купалы падрыхтавалі: д-ка Караліна Мацкевіч (куратарка); Натальля Райсанен, Павал Шаўцоў, Ігар Іваноў (тэксты і пераклады); Саша Белавокая, Майкал Сагаціс (здымкі). The digital exhitionion for the 140th anniversaty of Janka Kupała was authored by Dr Karalina Matskevich (curator); Natallia Raisanen, Paval Shautsou, Ihar Ivanou (texts and translations); Sasha Belavokaya, Michael Sagatis (images).