Адна з найбольш яскравых постацяў нашае выставы – вядомая паэтка і грамадзкая дзяячка Ларыса Геніюш (1910-1983). Палымяны патрыятызм афарбаваў ейную творчасьць і вызначыў драматычны лёс паэткі, якая прысьвяціла жыцьцё беларускаму нацыянальнаму руху.

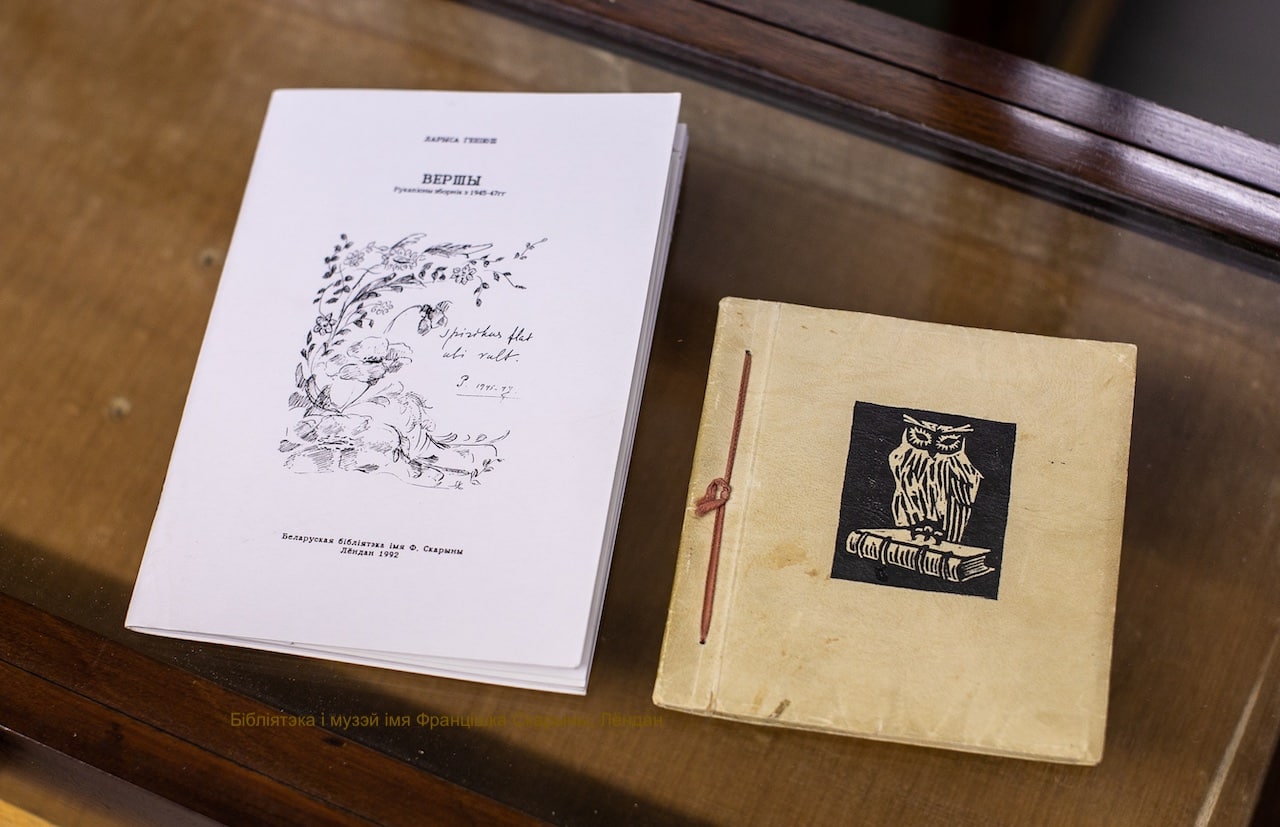

Л. Геніюш зь сям’ёй пераехала ў Прагу з Заходняй Беларусі ў другой палове 1930-х гадоў. Там яна стала сакратаркай Рады Беларускай Народнай Рэспублікі, уваходзіла ў Беларускі камітэт самапомачы і апекавалася беларускімі эмігрантамі, палітычнымі ўцекачамі і ваеннапалоннымі. Тут жа, у Празе, выйшаў ейны першы зборнік вершаў “Ад родных ніў” (1942).

У сакавіку 1948 году Л. Геніюш з мужам Янкам арыштавалі чэхаславацкія камуністы, якія захапілі ўладу падчас лютаўскага перавароту. Сям’ю выдалі савецкім спэцслужбам, якія патаемна вывезьлі іх у Менск. Сына Геніюшаў, Юрку, якому было тады толькі 12 гадоў, удалося пераправіць да сваякоў у Польшчу, у адносную бясьпеку.

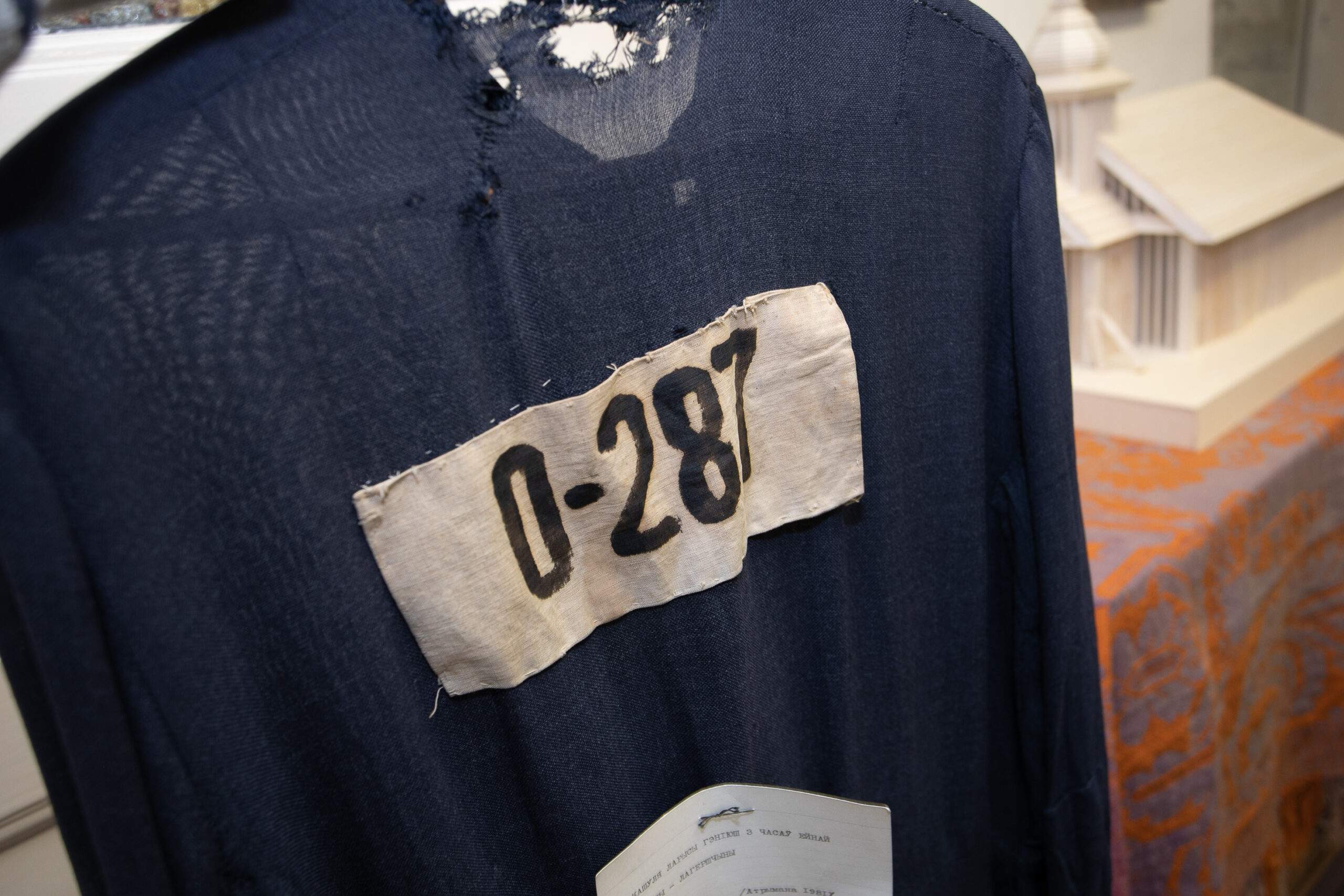

Падчас сьледзтва ад паэткі беспасьпяхова дамагаліся выдаць уладам архівы БНР, а ў лютым 1949 году Вярхоўны суд савецкай Беларусі прыгаварыў Ларысу і Янку Геніюшаў да 25 гадоў папраўча-працоўных лягераў. Л. Геніюш адбывала пакараньне на поўначы СССР, у 1956 годзе была вызваленая і разам з мужам вярнулася ў Зэльву Гарадзенскай вобласьці.

One of the most fascinating persons featured in our exhibition is a poetess and public figure Łarysa Hienijuš (1910-1983). She devoted her life to the Belarusian national movement. Hienijuš’s ardent patriotism greatly influenced her work and determined her dramatic fate.

Hienijuš and her family moved to Prague from western Belarus (then part of the Second Polish Republic) in the second half of the 1930s. There, she became the secretary of the Council of the Belarusian Democratic Republic and a member of a Belarusian Relief Committee that provided support to Belarusian émigrés, political refugees and prisoners of war. In Prague, her first collection of poems, From the Native Fields, was published in 1942.

In March 1948, Hienijuš and her husband Janka were arrested by Czechoslovak communists who had seized power during the February coup. The family was handed over to the Soviet security services who secretly transported them to Minsk. Hienijuš managed to send her twelve-year-old son, Jurka, to live with her relatives in Poland in relative safety.

During the interrogation, the poetess was pressured to hand over the archives of the Belarusian Democratic Republic to the Soviet authorities. She did not succumb to coercion. In February 1949, the Supreme Court of Soviet Belarus sentenced Hienijuš and her husband to 25 years in the Gulag camps in the far north of the USSR. They were released during the 1956 Khrushchev amnesty and returned to Zeĺva in the Hrodna region of Belarus.

У лягерах яна працягвала таемна пісаць вершы і вынесла адтуль адныя з самых балючых і моцных сваіх твораў. Разлучаная з сынам і мужам, асуджаная на прымусовую працу ў неймаверна цяжкіх умовах, Л. Геніюш засталася няскоранай у сваёй чалавечнасьці і адданасьці беларускай ідэі. У сваёй кнізе ўспамінаў “Споведзь” яна піша:

“З калень я ўстала другім чалавекам, па-новаму нейкім сільным і зусім спакойным. Для мяне існавала толькі цяпер мая Радзіма… Я ня ведала, што йсьці на сьмерць за Радзіму ня страшна, а лёгка, весела, амаль сьвяточна”.

Пасьля высылкі паэтка адмовілася прымаць савецкае грамадзянства, працягвала пісаць і выдавала сваю паэзію. Ейная гасьцінная хата ў Зэльве стала мейсцам таемнага паломніцтва для беларускай культурнай эліты 70-80-х гадоў.

While In the Gulag, Hienijuš continued to write poems in secret and produced some of her most sombre and powerful verses. Separated from her son and husband, and sentenced to forced labour in unimaginably harsh conditions, Hienijuš remained unswerving in her humanity and devotion to her homeland. In the book of memoirs, The Confession, she writes:

“I got up from my knees a different person, somewhat strong and completely calm in a new way. Only my Motherland existed for me then… I had not appreciated that choosing to die for the Motherland is not scary, but easy, joyful, almost celebratory.”

After the release, the poetess refused to accept Soviet citizenship and continued writing poetry. Her hospitable house in Zeĺva became a place of clandestine pilgrimage for the Belarusian cultural elite of the 1970-80s.